|

Into the Clouds

Richard Yallop & F/LT. Ron Patterson

April 1943 – July 1944

In April 1943 Ron and Doug received their first combat posting to the RAF's 152 Squadron in Algiers. The main role was ground support of Allied troops in the North African desert, through low-level bombing and strafing of enemy troops and shipping. The squadron's airmen were from all parts of the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The ground crews were all from the UK. Led initially by Squadron Leader John Eric James Sing then Squadron Leader Frederick Woodbridge Lister DFC, two Battle of Britain hardened Englishmen, the unit had a reputation for unruly, undisciplined behaviour. Arabs on camels straying onto the strip at Souk-el-Khemis would be warned away with 45 pistol shots; bored pilots, including Patterson, would shoot out the lights in their huts; if Sing did not like the gramophone record playing in the mess, he would throw it in the air and shoot it to pieces.

The runway at Souk-el-Khemis – like most that the squadron encountered during the war – was pretty rough. Often the strip would be covered in steel mesh to cover the potholes. Pilots had to taxi out as quickly as possible in order to take off quickly. Because of the fast speed while taxiing there was a danger that the tail would lift up, and if you hit any sort of bump the plane was likely to pitch forward, nose onto the runway. To keep the tail down, a member of the ground crew would hang onto it while the plane was taxiing then, as the pilot swung around into the wind for take off, the man would jump off. One guy forgot to get off quickly enough and found himself hanging on for dear life as the plane took off. The pilot realised at once that his aircraft was not flying as it should and, seeing the man on the back, did a circle and landed. Miraculously the man had managed to hold on – once down he collapsed on the ground in a state of shock.

Ron's first operational mission was to dive bomb a German cruiser stranded on a sandbar in Tunis harbour. The spitfires were equipped with a 250 pound bomb under each wing 152 was the first spitfire bombing squadron and the pilots found themselves engaged in an operation for which their planes had not been designed, namely aerial combat.

It was pretty hair-raising because you're suddenly in a vertical dive. No one hit the cruiser, and we had a massive red sheet of flak coming up against us. One of my Australian mates, Bob MacDonald, was shot down, but managed to walk back through the desert.

The squadron moved from Algiers to Tunisia, where it was stationed at Protville, located between Tunis on the east coast, and Bizerte on the north coast – some 35 miles (56 Kilometres) north-west of Tunis. Here the main task was to strafe German motor transport on the Tunisian roads. Ron came across a broken down Bedford van, abandoned by the German's and was able to repair it. He was now the proud owner of a vehicle. One day he and some mates went for a drive in the desert and came upon a small mosque. Among the Allied forces it was said to be bad luck to go into a mosque and Ron's friends resolutely refused to go inside. Ron's natural curiosity got the better of him and he ventured through the open entrance. There were two rooms, both in darkness as there were no windows. He moved through the first area into the second, whereupon he heard an unfamiliar and strange buzzing sound. When he came out he was completely covered in fleas!

Ron tore off his clothes and tried to wash himself down with the little water the men had with them. He threw his clothes into a drum of petrol. Still infested with insects, he climbed onto the bonnet of the van and told his mates to drive 'as fast as hell' so the fleas would be blown off!

|

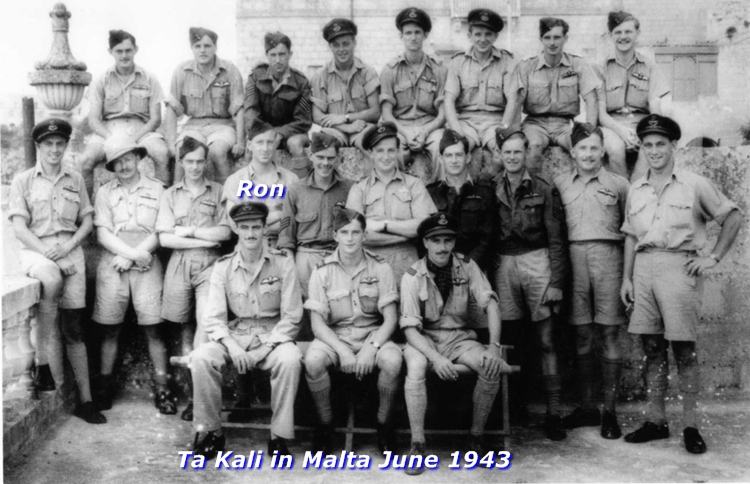

With the North African war won, the squadron was posted to Malta in June 1943, in preparation for the imminent Allied invasion of Sicily. Malta, a Mediterranean island colony of Britain, played a crucial role in the Allied war effort. It had the only British harbour between Gibraltar (1000 miles, 1609 kilometres to the west and Alexandria (800 miles, 1287.5 kilometres to the east, lying only 60 miles south of Sicily, was crucial for Italian supply lines to Tripoli before May 1943, when the Axis powers capitulated in North Africa. Between early 1941 and May 1943 the tiny island was subjected to constant bombing and the civilian population of 270,000 suffered heavy casualties. In 1942 the Germans mined the waters surrounding the harbour, which left the island virtually defenceless. The Luftwaffe, with bases on Sicily, conducted unrelenting air raids on the Maltese people who, often starved of supplies. Survived at barely subsistence levels. Many lived in caves and tunnels underground, but they refused to surrender. They became a symbol of resistance for the Allied cause and in April 1942 King George V1 awarded the island the George Cross. By mid-July 1942 most of the mines had been cleared and British submarines, based in Valetta harbour, were able to target Italian convoys heading to North Africa. The planning for the invasion of Sicily began as early as February 1943, and troops, ships and aircraft started gathering in Malta fot the assault. Ron's 152 Squadron was based at Ta Kali, an airfield in the centre of the island, lying due east of Mdina. The strip had been constructed by the RAF during 1940, then extensively expanded over the following three years. Established as a one-squadron fighter station, it had been laid down on the bed of an ancient lake and its grassy surface deteriorated quickly in bad weather while in summer it turned to baked earth. In addition to this, it had been subjected to heavy bombing during the German raids on the island.

The invasion of Sicily began on 13 July 1943. Ron narrowly avoided being shot down by friendly naval anti-aircraft fire during the assault as he was chasing a German fighter aircraft, a Focke-Wulf Fw-190. The squadron was providing aerial cover for the naval armada down below in the Mediterranean, and Ron peeled off to go after the Focke-Wulf. The German aircraft was not hit by the naval anti-aircraft fire, but Ron's plane was damaged so badly that it never flew again.

Once on the ground in Sicily, General Patton took control in the west while Montgomery, fiercely resisted by the German's operated in the east. 152 squadron was based at an advance airstrip, just behind the the front-line, at Lentini East, south-west of Catania (on the central east coast). The squadron soon came under fire.

'Our base was raided by the Germans. One night they bombed the hell out of us and we lost half our planes. Doug and I clambered out of our tents and dashed for cover under the nearest vehicle. To our horror, we discovered later that we had been sheltering under a fuel truck! One pilot was never found. 'We dug trenches after that episode.It was about a week before we were operational again. 'The runway at Lentini East was carved out of a vineyard with wire mesh laid down between the vines. Instead of the usual three planes taking off at once, there was not even enough space for two planes abreast. Two planes would take off together, with one wing of the second plane tucked in behind one wing of the first. There was no margin for error.' You kept your eyes glued on the spitfire in front of you,' Ron remembers.

In August, while still at Lentini East, Frederick Lister was replaced as squadron leader by Mervyn Bruce Ingram, a young but tough New Zealander with a distinguished service record. Ron recalls the first meeting with the new leader, whose boyish looks belied his flying ability and strength of character.

'When Bruce Ingram took over the unit in August 1943 he said, “I hear you're a pretty undisciplined squadron. Well, I'm going to straighten you out”, and he did. 'He was only a short bloke but he stood up on the table and pointed to the squadron leader's insignia on his epaulets. “See those,” he said. “I have just got them, and I do not intend to lose them through any bad behaviour or sloppy flying on your part. You have a reputation as a pretty lousey squadron, but don't think for one minute you are going to break me,” He brought discipline. I liked him. He turned our squadron into one of the best.'

|

Sicily proved a hard fight. The spitfires were involved in beachhead patrols and escorting the bombers. It was a scorching summer for the troops fighting on the ground in rocky and almost treeless terrain. Allied casualties were 23,000, of whom some 5500 were killed. Messina, in the far north-east – just across the strait from toe of Italy- was not taken until 17 August. Ron's squadron then moved to Milazzo East, on the north coast of the island, west of Messina, in early September, ready for the invasion of mainland Italy. The squadron compiled the highest strike rate of all the Allied air force units in the invasion of Sicily and mainland Italy, during July-September 1943. On 25 July Ron shot down his first enemy aircraft, a transport plane accompanied by a wing of fighters. It was one of eleven aircraft shot down by the squadron in Sicily that day. Ron's deeds were recognised in Italy- his promotion to a commissioned Pilot Officer came through on 6 August. The less glorious side of war was also apparent. Ron remembers some instances of looting. On one occasion in Sicily he and his Canadian cobber, nicknamed 'Hawkeye' used their initiative to satisfy their hunger pangs. They had noticed a farmyard with chooks and decided to approach the Sicilian farmer and ask for some eggs. It was daytime and to reach the farmhouse they had to walk along a narrow laneway, guarded by an extremely large and ferocious looking dog that was chained to the fence.

'As we edged our way along the lane the dog snarled and strained at the chain. We flattened ourselves against the fence on the far side and there was barely enough space for us to get past the frightening animal. I was somewhat concerned , to say the least, and drew my pistol, pointing it at the dog's head.' The farmer was less than impressed by the airmen's request for eggs, refusing point blank. Hawkeye seemed undaunted by this and, once out of earshot, told Ron they should return under cover of night. This time they approached the farmyard from another direction. Ron was appalled when again they encountered what appeared to be the same dog. This time it was lying down, making strange grunting sounds. 'There seemed to be something wrong with it. It seemed to be snoring but I wasn't convinced'. “What are we going to do about the dog?” I asked Hawkeye. 'He retorted, “For goodness sake, talk to it. Pat it and keep it quiet while I go and raid the hen house.” “Pat it?” I thought to myself in horror. I could still see the image of the snarling head in the laneway. I was scared stiff but tried not to show it. I picked up a heavy piece of wood and shakily approached the dog. I leaned over it, uttering reassuring words while feeling totally terrified. It seemed an age before Hawkeye returned with four or five chooks under his arm.'

|

According to Ron, looting on a more serious scale was quite prevalent by the advancing Allies, but he has no recollection of any looting by the retreating German troops.

Ron also admits to relieving a couple of Italian police officers of their revolvers.

'I had no authority, I was not a senior officer, but I went up to them and asked them to hand their guns over. They wanted something in writing from me, some sort of authorisation. So I pulled out a scrap of paper and wrote out the first few lines of “Mary had a little lamb,” which seemed to satisfy them!

On 3 September Montgomery took control of Reggio on the Italian mainland, just across the strait from Messina. He was to move northwards while the main naval and air attack on 8 September was to be carried out at Salerno, some 50 miles south of Naples. On the same day it was learned that the Italians had surrendered , but the Germans then took control of the country. As the squadron accompanied navel shipping for the invasion of mainland Italy at Salerno, Ron's engine failed. As soon as he turned-to try and make it back to Sicily- he warned the unit, but squadron Leader Ingram's response was abruptly dismissive:

'Shut up. Radio Silence.'

'I wasn't very happy at the time, and I know my mates weren't because the practice was that if you saw one of your unit spinning away, one of you would follow to see what was happening or at least try to pinpoint the location. The first trauma was what was going to happen to you in the drink? Who would see you? You had no life jacket or life raft, because of lack of space in the cockpit, and once you hit the water you had to unharness the parachute, and I did not know how long that would take. I felt angry about it at the time-angry that radio silence was more important than me killing myself.

'I was rapidly losing altitude. We had always been warned not to crash-land on water. It was imperative to bail out beforehand; otherwise the weight of the Merlin engine-aided by the aircraft's long and slender nose- would drag the spitfire front-on to the seabed. It would sink in seconds and take you with it. 'It was conventional flying wisdom that, if time permitted, the safest way for a Spitfire pilot to bail out was to stand up in the cockpit and kick the control stick forward, which in turn makes the plane pitch forward-the force throws you out of the cockpit and clear of the plane. On the other hand, if you climbed over the side it was quite possible to be struck by the tail.

'In an emergency, pilots were always warned to jump at a minimum height of 500 feet, giving them a chance to get the parachute open before it became engulfed by sea water. In dire circumstances you could try jumping at 300 feet, but that was dangerously low and would be a last ditch effort. The first choice was to make it back to base (in this case Sicily), or to crash-land on the ground, but failing those safer options, you bailed out as high as possible;

Just as Ron prepared to jump the first time, the engine spluttered back to life. The reprieve was short-lived. Ten minutes later, the engine failed a second time, and after spending a moment trying to re-start it, he once more prepared to parachute out. Standing on his seat, ready to jump, the engine came on again. All the time Ron was losing altitude and, now down to about 4000 feet and almost clear of the water, he was anxious about landing on the ground with the 90 gallon tank under the central fuselage-all his attempts to jettison it had failed. Finally, when he had his third cut out, the engine coughed, spluttered then stalled for good, and he was forced to glide into the narrow airstrip, which was cut between grape vines. Unable to do a 'belly-landing'- the safest option normally-because of the danger of blowing himself up with the under-fuselage fuel tank, he did what was, in the circumstances, a perfect landing with his wheels down. With no power he had no control-if the plane had crashed into anything it would have blown up.

'It was just fate. I was pretty lucky to get down',

Was Ron's modest summation of the outcome.

Salerno was fiercely defended and the Allied troops were in danger of being pinned down on the beaches. It was more than five days before they were able to move forward, backed by the battleships ans air force, and they did not reach Naples until 1 October. The front line, stretching 120 miles (193 kilometres) across the width of Italy, then prepared to move north towards Rome ( a move that was to prove far more difficult than the military planners had envisioned). Ater the initial invasion, 152 was one of the first fighter squadrons to land on enemy territory. It was stationed at Asa, one of the airfields on the Salerno beachhead. With a day off, Ron was one of four to go into the southern Italian city of Naples. Because the Allies had just arrived, there was no martial law and no central administration to look after the local Italians.

'People were hungry and we gave them tins of bully beef. It was terrible- we saw parents offering their daughters for food. It made me realise the most important thing in life is food, then warmth'.

During part of October and November 152 briefly sojourned at Gioia-del-Colle, a short distance inland from Bari on the coast of the Adriatic. The town of Gioia was little more than a small cluster of whitewashed buildings surrounding a medieval castle dating from 1230.

The Italian campaign, after the initial landings in the south, proved difficult and protracted – it was not until April 1945 that victory was achieved. The men of 152 squadron, however sailed to Egypt in November 1943. In Cairo, along with 81 squadron, they were re-equipped with the new spitfire V111s. They were to fly them out to India, where no spitfires had been used in combat, only Hurricanes. While waiting to leave, Ron and Doug spent the evenings in some of the local bars. One night they had a couple of girls with them and went dancing at a nightclub. Returning to their table after a dance Ron discovered that his wallet was missing.

'A waiter came up and indicated to me that I had left it on the table during the dance and that some blokes over in the corner of the room had taken it. The wallet had been tossed on the floor behind them. I went and picked it up-it was empty and I asked the men for my money back. There were five of them, tough Pommy army blokes. They just laughed at me.

'The two girls had moved towards the door. I became angry and the Poms became aggressive. They backed Doug and I against the wall and I picked up a chair to defend myself. Just when I thought we were going to be severely beaten up, a voice nearby said, “In trouble Aussies? Just stand aside”. Suddenly two enormous New Zealand Maoris pulled us away. They made short work of the five Englishmen, who were left rather worse for wear in the floor. The Maoris grinned at us, saying, “Good on you Aussies. Thanks for the exercise”.

I lost my money, but I wasn't going to stoop to searching the pockets of the fallen Poms'.

On 27 November, with a Mosquito accompanying them to navigate, Squadron Leader Bruce Ingram led his airmen in thirteen hops to India, including Bahrain and Karachi, and finally arriving in Baigachi near Calcutta on 30 November. 81 squadron was posted to Alipore.

'On the way out we lost one of the pilots when he misjudged the runway taking off from Bahrain and crashed into the sea. It was a long way, carrying 90-gallon overload tanks full of fuel. Overall, we did very well and it was all due to Bruce Ingram'.

The squadron commenced combat duties on 19 December as part of the defence of Calcutta. Defensive patrols were carried out over the city and offensive sweeps were made against Japanese airfields in central Burma. At the end of the first week Ron shot down the squadrons first Japanese aircraft, a Dinah. He hit the twin-engine reconnaissance aircraft at around 33,000 feet-the highest-altitude strike achieved in the Japanese theatre of war. It went down as a joint strike by Patterson and his Australian friend and section leader, Flight Lieutenant Bob MacDonald. In his sortie report, MacDonald wrote that he and his No 2 Pilot Officer Patterson, were scrambled at 0805 on 26 December 1943 to intercept a high-flying enemy aircraft. Ron recalls the incident thus:

|

'We both took off and climbed steadily. We had been told where the aircraft was and we sighted it in front of us at about 33,500 feet. We had the sun behind us and initially the pilot did not see us. We closed in behind and finally he must have seen us because a white flak-like burst appeared in front of us'.

Neither Ron nor Bob felt any effects from the blast but Bob, on landing, reported 'two or three small holes in my nose and wing'. Ron remembers that after the enemy aircraft shot the missile,

'Bob fired at it. The recoil of the guns then sent him spinning out of sight. After seeing what had happened to Bob, I did not fire, knowing that if I missed we would never catch the Dinah'.

Inexplicably the enemy aircraft then went into a shallow dive. Knowing that he had him Ron gave chase and closed the gap.

'If he had climbed I would have lost him. But his defensive dive, to get speed-the reaction of fear-enabled me to increase speed, which stabilised the aircraft at that altitude. I was very close to him when I opened fire, and because of my speed I did not spin out as Bob had done. The enemy aircraft caught fire and went into a spin'

In his report MacDonald said :

'As my No 2 went down after him I saw him score many strikes firing from the port quarter. The port engine of the Dinah caught fire and a large chunk fell off the port wing about halfway along the trailing edge... I consider that the chances of catching this aircraft, assuming it is flying at maximum speed at this altitude (33,000 feet), are slight if it has a start of a mile 1.6 kilometres.

As a result of his actions, Ron was promoted to Flying Officer in early February 1944.

When Ron's squadron arrived in eastern India at the end of 1943, the Japanese had occupied Burma since mid-1942. Burma, bordered to the north and west by the Indian provinces of Assam, East Bengal and Manipur, was characterised by jungle-covered mountains with a dry plain in the centre. The weather was dominated by the tropical monsoon between May and October. Four of Asia's largest rivers flowed through the country: the Irrawaddy, Chindwin, Sittang and Salween. For an advancing army, the terrain and the weather posed a strategic nightmare.

The Allies had made some attempts to advance on to the coastal plain of the Arakan in south-western Burma in September 1942, but the campaign had floundered by early 1943. In October of that year, Major General William Slim assumed command of the British 14th Army, based in eastern India. By the end of the year, the Japanese had two plans: to further their advance in the Arakan; and to destroy British strongholds around Imphal, the capital of Manipur, near the north-western border of Burma.

|

Imphal, at the centre of a plain some 30 miles wide and surrounded by high, forested hills, was essential as the advance base for maintenance and operation of Allied land and air forces in the area. It was located on the main line of communications between India and Burma, but there were six approach routes to the plain. The key to success was to hold the high ground. If Imphal and its surrounding supply depots fell to the Japanese, the British would be deprived of their springboard for retaking Burma, and the Japanese would get an advance base from which to conduct operations against India. On 6 February 1944, the Japanese started their offensive in the Arakan, and a month later made their move against Imphal. They planned to advance from all sides, hoping to take Kohima, in the Indian province of Nagaland and 140 miles (225 Kilometres) north of Imphal, before moving south to meet up with other troops advancing along the road from Tamu (inside Burma and south-east of Imphal). As it turned out, these latter troops were blocked from reaching the Imphal plain by the British.

In the north, the Japanese cut off all roads into Kohima. At the isolated airstrip, 3500 Allied troops faced 15,000 Japanese during a ten-day siege before reinforcements were able to relieve them. Kohima was miraculously held, with Japanese casualties numbering 4000 dead. The Allied commander, General Slim, admitted to the complexities of the situation, starting: ' The story of the prolonged and hard-fought battle of Imphal-Kohima... is not easy to follow. It swayed back and forth through great stretches of wild country, unpronounceable village a hundred miles away.'

It was in this theatre of war that 152 squadron took up combat duties. Initially there was little air activity as the Japanese army and air force were seriously overstretched. The period of relative calm ended in February 1944 when Japanese ground forces went on the offensive in the Arakan. The Japanese engaged in guerilla tactics, infiltrating behind Allied lines and cutting supply routes, hoping to force a retreat . British troops were told to hold their positions, and the spitfires were used to maintain air superiority , thus enabling transport planes to supply the troops until they could be relieved.

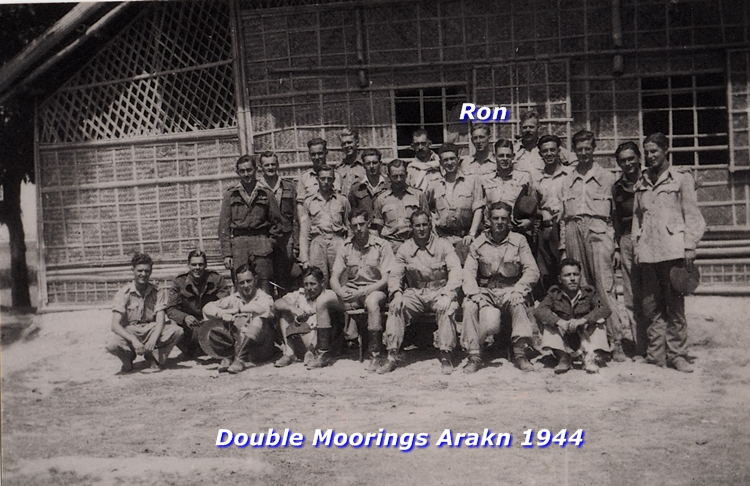

From February 81 and 152 squadron's were moved to a series of bases straddling the India-Burma border. A detachment of the 152 moved to Ramu, from where they engaged in offensive patrols and escort missions, accompanying heavily laden Dakota transport planes. No 81 squadron was posted to Tulihall, some 20 minutes by air south-west of Imphal, working mainly with the 14th Army. A detachment of 81 was stationed at 'Broadway', 200 miles (322 Kilometres) behind enemy lines with Major General Wingates troops, who were engaged in Operation Thursday, launched on 5 March 1944. 152 was posted to Chittagong, on the north-east coast of the Bay of Bengal-on the Arakan front. (Chittagong was a coastal city in one of the provinces in north-east India before the war; in 1947 it was incorporated in East Pakistan, and is now the second largest city in Bangladesh.)

|

'When we landed in India we thought we were top pilots. We thought we knew it all so we felt insulted when the air force sent a Polish pilot out to give flying demonstrations of the spitfire. He was to pick up one of our aircraft and visit Hurricane squadron's to demonstrate the tremendous performance of the spitfire V111. We thought we could have easily performed this task. He landed at our base in a Tiger Moth and we watched, without showing much interest, as the CO selected one of our spits for him. He took off and climbed to about 1000 feet-then he looped the plane, an almost impossible feat in a spitfire at that altitude. We were awestruck but no sooner had he completed this action than he swooped down to about 20 feet off the ground and flew past us upside down. It was an amazing display; he was an incredible pilot and none of us had ever seen anything like it.'

At Chittagong the squadron was engaged in fighter patrols, making offensive sweeps against the Japanese airfields located inside Burma. It began patrolling the Imphal plain as well as escorting transports and bombers. As Japanese air activity decreased the unit also attached enemy supply lines and carried out small-scale attacks on ground targets of opportunity. One of the worst problems for the pilots was the weather. Ron recalls an extremely close call. Ordered on a routine surveillance mission from its base at Chittagong, the squadron had reached its cruising altitude of 22,000 feet, when it flew into a huge tropical storm. The spitfires were thrown around like balsawood models, powerless in the face of the buffeting winds and rain.

'Normally you go over or around a storm, but this time we couldn't because the front was so big. Once we were in it, we were all over the place, and lost control. My aircraft lifted and dropped, stalled and went into a vertical dive at 600 miles per hour. The controls froze because of the force of the airflow over the wings, and even partially standing and using full strength I still couldn't budge them. I slumped back into my seat, dropped my hands in despair, and in doing so touched the trimming tabs control. This was a small wheel next to the seat that operated very small tabs in the ailerons for trimming the plane in normal flight. In panic I grabbed and turned it. Those small tabs were able to pull the plane out of the dive, and in doing so caused me to black out. This would happen under high G-force, drawing the blood from the upper part of the body, and causing temporary loss of sight. When my vision returned I found I was in a vertical climb, and was able to regain control of the plane. I managed to make it back to Chittagong, but the aircraft had damage to the wings and the next day was totally written off when it was hit by a petrol truck. From recollection, four pilots and aircraft were lost that day.'

The experience of putting the spitfire into a dive such as that experienced by Ron is described by spitfire ace, Alex Henshaw, in his 1979 book Sigh for a Merlin. He described it thus.

'The first series of (dive) trails only confirmed what I already knew: there was a reasonable safety margin when dived at any height with full power. I then decided I would dive the machine to its utmost terminal velocity speed. I climbed to about 37,000 feet and pushed the nose over in a vertical dive. This was not really successful as the engine cut in the early stages if I applied too much negative “G” and if I kept the engine in power the angle of the dive was not steep enough. In the final dive I did a level run at 37,000 feet for some few minutes and then half rolled straight into a vertical dive; the technical department at Castle Bromwich had not been able to provide me with a calibrated airspeed indicator (ASI) so I shall never know the exact speed in that particular dive. On the ASI I was able to read off between 560 and 570 IAS and the revs did in fact go 100 over the maximum permissible, but this took place at only one critical phase.

'The interesting thing about the test was that the ailerons, as expected, went rock solid at about 400-450 IAS onwards and then the elevators. I had taken the somewhat puerile precaution of not fastening my safety harness so that if the machine broke up I might have a chance of being thrown clear; but lacking the comforting feel of the shoulder straps I felt as if I were almost naked. The spitfire hurtled earthwards with the controls rigid and, at the angle at which I sat when I put some pressure on the control column it moved me easily from my seat. The utmost delicacy was needed to ease the machine out at that speed and, as I could not pull the control column back, I used the trimmer tab as if it were as fragile as a biscuit. The machine pulled out quite easily and I felt more relieved and certainly happier than I had been before.'

'There was one big difference,' Ron says. 'Henshaw knew what he was doing, and I didn't.'

In fact, luck and a panic response had saved Ron from hurtling to his death. Ron had now been with the squadron for some sixteen months. Continually seeing comrades and cobbers die had begun to make him increasingly weary of war and combat. He was also weary of the sometimes poorly judged and poorly briefed decisions of the desk-bound officers who issued the orders. While he was based at Chittagong, someone at Allied headquarters in Delhi decided to give the Japanese a jolt on Emperor Tojo's birthday by sending 152 squadron to strafe the enemy at the heart of its defence in Mandalay, in central Burma. But the officers responsible for the decision failed to take into account that the range of the new spitfire V111s even with extra fuel tanks fitted, was insufficient to reach Mandalay and last for any combat time. In fact, they didn't even know 152 squadron was flying spitfire V111s; they thought they were flying the long-range US Liighnings.

The squadron did reach Mandalay and strafed the airport, destroying a number of enemy planes, and headed back hastily to Chittagong without having to engage the enemy in aerial combat. One pilot had to bail out into enemy territory when he was unable to switch on his reserve fuel tank. Luckily, he was helped back to Allied lines by friendly Burmese. The squadron's intelligence officer rang Delhi to complain about sending planes without the range to engage in combat with the enemy, and it was then that officers admitted they thought the squadron was flying Lightnings, with double the range of the spitfire.

'I'm not for war, though I recognise in certain circumstances it's necessary,' Ron says. 'I think the bloke who authorises the action should be there, not some bloke at a desk. Later at Courtney & Patterson, I did everything; I cleaned the toilets and I worked for hours under engines. If you're going to be good at anything, you've got to have a hands-on approach.'

Some weeks into the squadron's posting to Chittagong, Ron wrote flatly in his diary that the squadron had lost five pilots in accidents in the previous twelve days of operations. The tone was clipped and seemingly unemotional. He expressed no fear for his own safety but this detachment, he recalls, was merely a front.

'My log entries were fairly brief. By the later stages I'd had enough of the war. I'd flown 271 hours of combat missions (without rest-we were continually on duty), and it doesn't sound a lot, over twelve months, but as you go on you get concerned when you see other people no longer there. I think there's a fear that builds up, which you don't express. Most people feel fear, but you have to overcome it. If you feel fear you have this great adrenalin rush. As soon as you start the motor and get airborne, the fear's gone. 'You sometimes hear courage defined as a lack of fear. I believe a bloke has no courage if he says he experiences no fear. Courage is having fear and overcoming it.'

On the 17 April the squadron was moved a few miles north to Rumkhapalong and, much to Ron's annoyance, an officer made a decision to ground him pending an eye test for his shortsightedness. Incensed, Ron said the problem was caused by the glare of flying in North Africa desert in 1943.

'I said, “Its ridiculous, I've been flying so long without crashing planes or getting into trouble”.'

Nevertheless, he found himself in charge of transport to Comilla, the squadron's next base some 160 miles north-west of Chittagong. The pilots had flown the spitfires there on 6 May and Ron was to organise the relocation of the ground crews and support vehicles. The weather was poor, but despite this the squadron was flying two days a week to the Imphal plain, north-east of Comilla.

On 16 May Ron was required to fly to Calcutta for the dreaded eye test. The outcome was that he could not fly combat missions again until he received glasses. He was to wait for the arrival from England of a pair of flying goggles with special lenses.

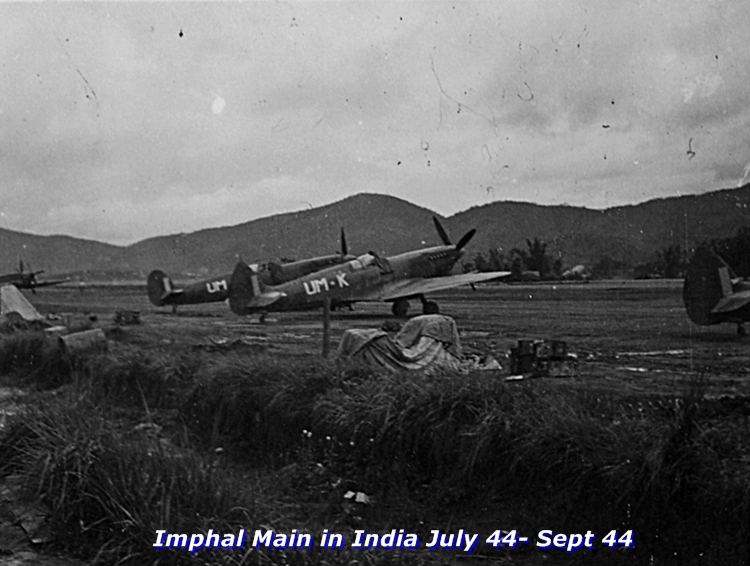

On 31 May the squadron moved closer to Imphal, this time to Palel, where an all-weather strip was situated at the southern end of Imphal Valley. The men lived in grass huts overlooking the airstrip. Once again Ron was left behind in Comilla this time, to organise the transport of ground staff, and forty Indians, During June the squadron was engaged in escorting supply planes into Burma, hampered largely by the awful monsoon weather. When Ron finally arrived in Palel on 13 July, it was to learn some terrible news. His much-admired squadron leader Bruce Ingram, had died two days beforehand.

In early July, returning from a ground strike, Ingram had blown a tyre while coming into land. In the crashlanding that followed the squadron leader broke his nose and severely lacerated his face. He was taken to a field hospital at Imphal but developed malaria then tetanus and died from the infection. (Ingram was replaced by a South African Major Harry Hoffe.)

The same month saw 152 move north to the air base at Imphal. Ron was devastated by what he saw.

'A combat unit of Wingate's attached to the 14th Army, was up there. It had been working behind enemy lines. We were there when they came out and it was one of the most disturbing aspects of the war for me. I had never seen men in such a state of deprivation.'

The Japanese siege of Imphal had finally been defeated by the arrival of the monsoon season. The Japanese troops, expecting to succeed in their offensive, had planned to live off Allied supplies. Without any air support, the Japanese troops were facing starvation and started to retreat. There were 53,000 Japanese casualties. By the end of June General Slim's 14th Army was advancing against the retreating Japanese towards the River Chindwin. It was the start of the Japanese defeat in Burma (Mandalay was captured in March 1945 and Rangoon in May the same year) and 152 squadron continued to support the 14th Army for the rest of the war. When 152 moved to Tamu in October 1944, it was the first squadron to re-enter Burma. It became known as the Black Panthers of Burma (the black panther, the emblem painted on the side of the spits, had been designed by one of the NCO's F/O. Len Smith DFM).

The role of the spitfire V111 in Burma had been a crucial one. Powered by a 1520 horsepower Merlin engines, the aircraft had a top speed in excess of 400 miles per hour. From November 1943 when 81 and 152 squadron's arrived, and particularly after mid-1944 when the plane was fitted with additional 45-gallon fuel tanks, the spitfire was capable of long-range escort and strafing sorties in the interior of Japanese-occupied Burma. From February to June 1943 the aircraft ensured air superiority during the Allied airlifts and only three transport planes were shot down.

On 26 July 1944 Ron was given a month's leave while awaiting the arrival of his glasses. He thought he was going to return to combat but this did not happen. Personally, he left stale, and tired of war.

'I got sick of it in the end, and the operational accidents that happen. Like the mate who didn't turn on his oxygen, and the rest of the squadron watching helplessly as the stricken pilot's plane spun to the ground, out of control. You can only do it for so long 'I always turned on my oxygen when the motor started so I would not suffer from lack of oxygen in an emergency.'

Ron, by now Flight Lieutenant Patterson, was posted from 152 squadron to non-combat duties in Madras. Here Ron met up with Bob MacDonald and they returned to Australia together. The disillusionment Ron felt as he sailed home from Bombay just before Christmas 1944 was in stark contrast to the exuberance of youth he had experienced when he had first started to fly in 1941.

Ron is welcomed back home home by his family and Lorna (Right to left): Dudley Carter (Gwen’s fiance), Gwen, Ron, Lorna and Ron’s father and mother

Ron Married Lorna on the 28th April 1945

This was all taken from the book A Business of Trust by Richard Yallop 2007

Ron is now 91 (01.12.12) and lives in Victoria Australia.

Ron sadly passed away on 18th January 2021 at the grand old age of 99

|